By Carolyn Williams

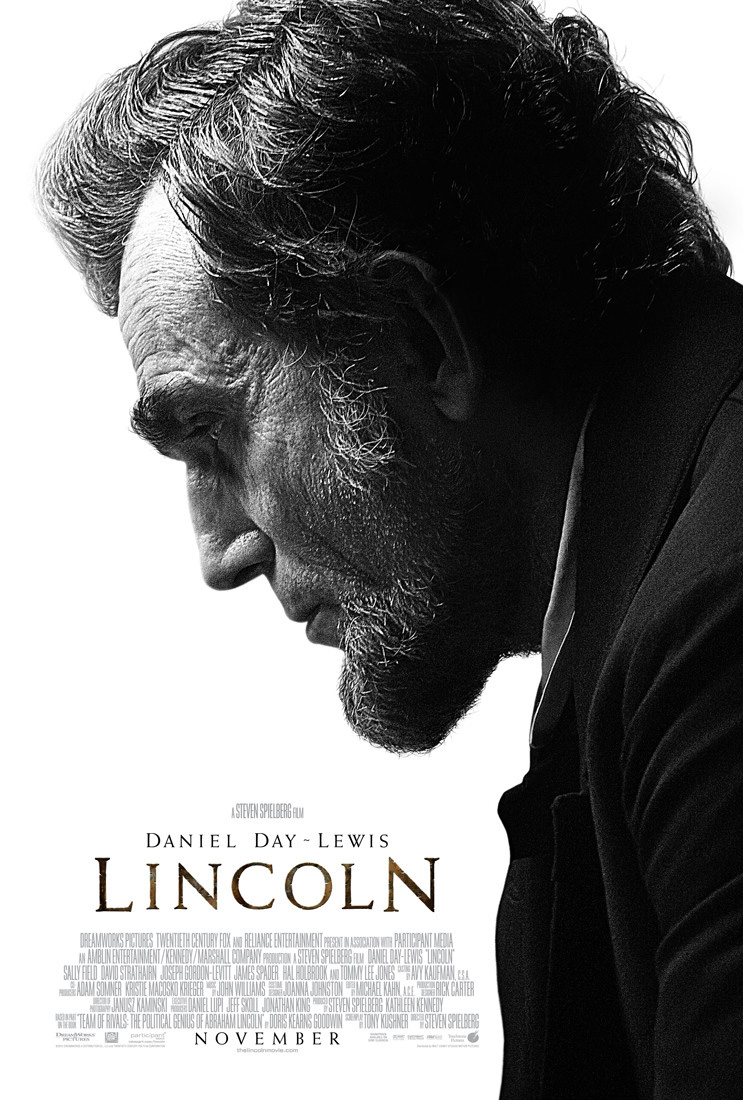

Steven Spielberg’s latest film, “Lincoln,” has been billed as a biopic of monumental proportions. In reality, it’s not so much a biography of Lincoln himself as a pointed interpretation of the process of passing the controversial Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution.

It’s 1865. Fresh off his 1864 reelection, Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), is keen to push the proposed Thirteenth Amendment through the House of Representatives before the end of the Civil War. Realizing that completely abolishing slavery will only fly if the South has not reentered the Union to fight against its being passed, Lincoln knows the clock is ticking. The longer the war goes on, the more Americans on both sides die, but he just needs a little longer to serve morality. But just to be sure things turn out the way they should, Lincoln hires men to ensure certain Democrats vote his way.

The reality of the devastation wreaked by the Civil War is underscored by the Lincoln family’s own precarious happiness. With one son dead of illness three years before, and another desperate to join the cause, Lincoln only takes time out of his dizzying schedule to be with his youngest boy, Tad, who brings comic relief to most of his scenes. But Lincoln’s wife, Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Fields) creates more problems than she helps solve, as she tries again and again to violently demonstrate her grief over her dead son, and her steadfast opposition to allowing Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), the eldest, to assert his independence by fighting for his father’s cause. Her dubious mental health clearly weighs heavily upon Lincoln, another burden for an already overburdened man.

But Lincoln manages to keep his troops smiling, both on and off the battlefield. Day-Lewis’s Honest Abe is a homespun scholar, delighting in the sharing and telling of silly, but always pertinent anecdotes, and the occasional quoting of Shakespeare or Pythagoras. Day-Lewis attempts to reconcile the massive shadow of one of American history’s greatest men with the reality of the fallible human he actually was. And his performance is genuinely spectacular.

“[‘Lincoln’ was] eccentric, though Daniel Day Lewis’s performance as Lincoln is powerful nonetheless. He is the Lincoln we hope existed, charming yet sagacious, the beneficent father of America,” Liz Walker ’14 said.

To be frank, Spielberg bends the truth a little with “Lincoln,” not that we wouldn’t expect the same of any director with this sort of a film. Such a beloved figure as Lincoln inspires total confidence in an American audience, and Spielberg takes full advantage of this general understanding of one of our favorite presidents. There’s a reason he’s on both the penny and the five dollar bill, after all. But even if “Lincoln” glosses over some of history’s more realistic reasons for the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment, it does make a concerted effort to act somewhat believably. When asked what he’ll think when African Americans have their freedom, Lincoln replies, “Well, I suppose I’ll get used to it.” And we, his fans, suppose he would have.

But all factual inaccuracies aside, “Lincoln” is a blockbuster for a reason; it’s fantastic to watch. With sparkling dialogue and a stellar cast, (particularly Tommy Lee Jones as the recalcitrant radical Thaddeus Stevens), “Lincoln” is a pleasure.

“Spielberg has done it again. ‘Lincoln’ took a historically powerful and intimate look at one of America’s favorite presidents. Recommend to all!” Emily Conners ’14 said.

Honestly, whether you’re a history buff or not, I can’t see many people disliking this movie; it’s just that good, and definitely one of this year’s strongest Oscar contenders.